China’s highly anticipated electricity sector five-year plan was released earlier last month but was criticised by the environmental community because it targets increased coal power capacity and slower growth for renewables. But as China’s economy adjusts to the “new normal” of lower economic growth, it is efficiency that should be the focus because this matters more than capacity as an indicator of China’s clean energy transition.

The electricity sector plan, released by China’s National Energy Administration (NEA), is a subsidiary of the 13th Five-Year Plan for Economic and Social Development (2016-2020) and delivers specific guidelines and targets to inform policy making, government spending and project planning in the power sector. Subsequently, five-year plans for wind, hydro, and grid companies have also been released.

The development of China’s five-year plans is a bargaining and bureaucratic process within the political system that includes local interest groups such as the coal industry. Although the targets set an approximate trajectory for the power sector, China has adjusted energy targets between five-year plans in the past, and will have the opportunity to revisit these targets over the coming years to increase ambition by 2020.

Increasing coal capacity

One major criticism of the plan is its call for new coal plants, in spite of existing coal overcapacity and flat power demand. China’s 2020 target for coal capacity of 1,100 gigawatts, an increase from 920 gigawatts, implies that as much as 45 gigawatts per year of additional coal power will come online over the next four years, though some old capacity will be retired. Each new gigawatt of coal energy represents as much as US$ 1.75 billion in unnecessary spending, which ultimately pays for physical resources and labour that could be allocated to more productive activities in the economy. Alternatives include investment in cleaner energy or in private sector services and technology innovation, the country’s future economic drivers.

The new target appears to contradict policies calling for many provinces to cap coal consumption and for large areas of China to set regional “red line” limits on new coal plants.

However, it is not surprising that China is still adding coal capacity given the importance of the coal industry to provincial revenue. Although China is making great strides in reducing coal consumption – coal use fell in the first eight months of 2016, according to the National Development and Reform Commission – government revenue is still the top priority. While completely eliminating approval of new coal plants would be ideal, both economically and environmentally, policymakers do not yet see this as a realistic option. Meanwhile, with some 200-300 gigawatts of coal capacity already given approval or under construction, the NEA has said that staying under the new, higher, 2020 coal power target will still be a challenge.

The idea that limiting coal plant construction by state-owned power companies is challenging, even when the government has recognised the overcapacity problem for years, lays bare the systemic biases that favour over-investment in generation assets.

Crucially, the higher capacity target for coal won’t necessarily determine how much of it China actually burns. What matters more is the efficiency of the power system as a whole, and ensuring that the most efficient power plants are given dispatch priority while the less efficient ones are phased out.

Renewables slowdown

A second criticism of the plan is it sets a slower growth rate for clean energy such as new wind and solar. Originally, the market expected 150 gigawatts of solar PV for 2020 (up from around 65-70 gigawatts today), but the new plan sets the 2020 target at 110 gigawatts. Similarly, speeches by top officials had suggested an increase from today’s 150 gigawatts of wind capacity to 210-250 gigawatts by 2020. This has been revised downwards to 210 gigawatts, the lower end of the government’s earlier guidance.

As disappointing as the lower capacity targets may seem, it’s important to note that China’s economic slowdown, along with structural changes to the economy towards a more consumer- and services-focused model, will have a profound impact on future demand and actual energy use, regardless of forecast capacity requirements.

Focusing on capacity made sense during the country’s period of rapid industrialisation, when electricity shortages could emerge quickly and China’s state-owned power sector needed to be pushed forward aggressively to meet the economy’s enormous need for power. The rush for capacity in renewable energy also helped scale up wind and solar quickly, helping the technologies mature and costs to fall.

But today, as China’s economy adjusts to the new normal, what matters more than capacity is efficiency, often at a provincial or regulatory level. Because of poorly coordinated development and distribution, as well as misaligned incentives, China wastes as much as 20% of the clean energy it produces. This wastage helps to explain why China produces less energy from wind than the US despite having significantly more installed wind capacity.

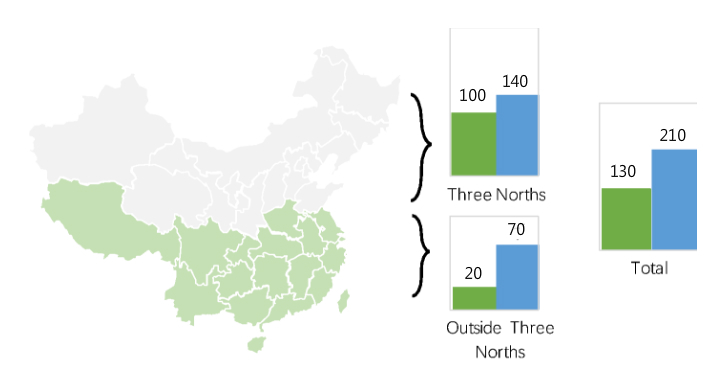

The good news in China’s latest Five-Year Plan is that it sets a clear quantitative target for reducing such wastage, called curtailment, below 5% by 2020. China’s newly released 13th Five-Year Plan for the wind sector further sets out targets for capacity by province, while also specifying a target for wind energy output – not just capacity. The plan specifies a maximum limit for new capacity in each province in the northern half of China, known as the “three norths”, where wind power is severely curtailed at present. Elsewhere in China, the NEA has assigned minimum capacity targets by province. The plan states that 57% of new wind capacity will be installed in provinces outside the “three norths” and that the “three norths” provinces should largely resolve wind curtailment problems by 2020.

Wind capacity: year-end 2015 and 2020 target (gigawatts)

Source: NEA

A quick calculation shows why this strategy isn’t as bad for the wind sector as it sounds: In 2015, China’s wind sector produced 18.6 billion kilowatt-hours, with curtailment of 15%. Assuming capacity increased to 250 gigawatts nationwide by 2020 and that the level of curtailment remained the same, 410 billion kilowatt-hours would be produced over a full year. China’s new capacity target is 210 gigawatts, but includes measures to reduce curtailment below 5%, and shift new additions to provinces outside the “three norths” that currently have little curtailment. Assuming these targets are realised, 210 gigawatts would produce 400 billion kilowatt-hours, just slightly less than the 250 gigawatts base case, but at only 84% the cost.

For comparison, the 13th Five-Year Plan for wind calls for the wind sector to produce 420 billion kilowatt-hours in 2020. This goal includes measures such as larger turbines and deployment of offshore wind.

2020 wind production targets under three scenarios, compared to 2015 output

Source: Paulson Institute calculations

To meet these goals, China needs clear plans and better coordination between agencies to integrate the country’s diverse energy sources into an efficient market. In recent months there has been a rapid roll-out of bilateral power trading pilots, new regional power trading centres (including in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region), and efforts to develop spot markets for renewable energy.

Next year, China is expected to launch a nationwide carbon trading market, and environmental taxes for smaller emitters. And China’s newly released five-year plans for the wind and power grid companies consider integrated planning and improvements to renewables integration at the regional level. Implementing these reforms will not be easy, and may conflict with long-established institutional incentives that have hindered power market reforms and renewables integration.

Looking ahead, capacity numbers and targets may be the least important indicator of how smoothly China’s transition to low carbon energy takes place. Instead, China can do more to clarify how its various energy-related agencies, targets, and policies will work together to create a more efficient power system and speed up its clean energy transition.