The Thai government has ambitious plans to modernise the country’s economy by transforming three provinces east of Bangkok with smart cities, high speed rail, new ports and airports.

In November, Deputy Prime Minister Somkid Jatusripitat led sales pitches to Chinese investors when he took government officials and 65 Thai private companies to Shanghai to promote the project, known as the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC), at the First China International Import Expo (CIIE) in Shanghai.

Somkid met with China’s Vice Premier Han Zheng in Beijing to talk about Thai-Chinese economic cooperation, according to China’s Xinhua news agency.

The Thai government has been keen to involve China from the beginning, and previously described the EEC as a “support valve” for China’s immense global network of infrastructure projects known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Big vision

Thailand’s manufacturing base needs a major upgrade, so the government has come up with its own macro-economic grand plan – which it calls “Thailand 4.0” – to transform its heavy industrial base into a more nimble digital and innovation-based economy. The EEC is a key part of this vision.

In the 1980s, Thailand opened up to international investors, especially Japanese automotive and electronic companies, to establish export-oriented manufacturing. By 1988, its GDP was growing at 13% per annum. But by the turn of the twenty-first century growth had stagnated, averaging 3% to 4% a year. Thailand 4.0 and the EEC are designed to tackle over-dependence on outdated manufacturing technology and cheap labour that has plunged the country into the so called “dark decades”.

Local pain

To many people though, the EEC already feels like a disaster. Prakob Singhanat, 60, and his family of 10 have been ordered to leave the rice farm in Bang Nam Priao district founded by his grandfather. They’ve had an official letter ordering them to vacate and seen distant groups of military and government officials wordlessly inspecting the neighbourhood in EEC-belt Chachoengsao province.

They have heard of plans for a new smart-city with high-speed railways, a digital hub, and innovative industrial zone. The project promises tens of thousands of jobs once investment arrives from Thai conglomerates, foreign investors and multinationals.

“But no one has ever come to talk to me,” says Prakob angrily. “I only know that if I and my family must leave this farm, we have nowhere else to go.”

Another 635 people are threatened with eviction from land totalling 1,580 acres. They have farmed there for three generations but have no legal title to the land, and were unaware that the land they cultivated was being passed from one private owner to another before ending up in the hands of the state.

Fifty kilometres away, land brokers have told yet more farmers to leave and make way for an EEC high-tech industrial zone. None of them are preparing to move out.

Small victory

The EEC was launched by Thailand’s military government but there was minimal public participation in drawing up the plans. Land rights have since become a major topic of public debate as the EEC requires a lot of land for new industrial zones and infrastructure.

The EEC legislation passed by parliament in early 2018 gives investors many privileges, including land ownership rights or long leases on state land of up to 99 years, plus low corporate income tax and import duties exemption.

The farmers at Bang Nam Priao have been protesting against eviction for nearly a year. In October, they won a partial victory when the EEC Office – the official government body promoting the EEC – dispatched its deputy secretary general Tasanee Kiatpatraporn to talk to them. She said the government had no intention of using farmland in the area for the EEC and promised public consultations on any decisions.

Courting China

Meanwhile, the EEC plans gathered pace in November as the Thai government wooed Chinese investors.

During the Shanghai expo, Somkid met executives of Huawei and ZTE Corporation, and called on them to invest in the EEC’s digital industries and Thailand’s development of 5G. He reportedly held a second official meeting with Alibaba Group executive chairman Jack Ma, a major public supporter of the BRI who in April promised to pour 11 billion baht (US$333 million) into the project for digital business and tourism promotion, big data facilities and e-commerce training for local entrepreneurs.

Thailand 4.0 and EEC mega projects have a lot of potential to coordinate with the BRI

In China, Somkid declared that the year of 2019 would be the “golden year of investment” in Thailand, and ordered the Board of Investment to design a new package of investor friendly policies.

Apparently, Chinese investors are the main target of this new package. Somkid sees rising opportunities to link Thai markets to the BRI, especially as the US and China trade war may prompt Chinese investors to look for new investment destinations and markets to avoid the additional tariffs on Chinese products imposed by the Trump administration.

BRI synergies

Chinese officials assess the national economic policies of every country that participates in the BRI to look for ways to coordinate them with the global initiative. “It’s also happened in Thailand where the Thailand 4.0 and EEC mega projects have a lot of potential to coordinate with the BRI,” says Dr Aksornsri Phanishsarn, an expert on Thai-Chinese relations at Thammasat University’s Faculty of Economics.

There are geographical synergies too with one of the BRI’s six “new Silk Road” economic corridors, the China-Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor. China identifies Thailand as “the most significant and fundamentally robust country in this peninsula,” says Aksornsri.

China is likely to get shares in most of the infrastructure projects

Further similarities exist between Thailand’s EEC and China’s “Made in China 2025” strategy. China is seeking to upgrade existing hi-tech industries through digitisation and the EEC plan strives to attract those same industries, especially aviation and robotics. Coordination within the BRI framework could strengthen Thai-Chinese supply chain networks and expand export markets.

“However, Thailand must be cautious,” says Aksornsri, adding, “China seems to use unilateral decision making in dealing with its BRI counterparts and there’s also a lack of transparency and good governance under BRI projects”.

Transport infrastructure

Along with attracting new investors, there are key EEC infrastructure goals for a “seamless” transportation network between Bangkok and eastern Thailand, and an overland route to transport Thai goods to southern China via Laos that connects Thailand into the BRI.

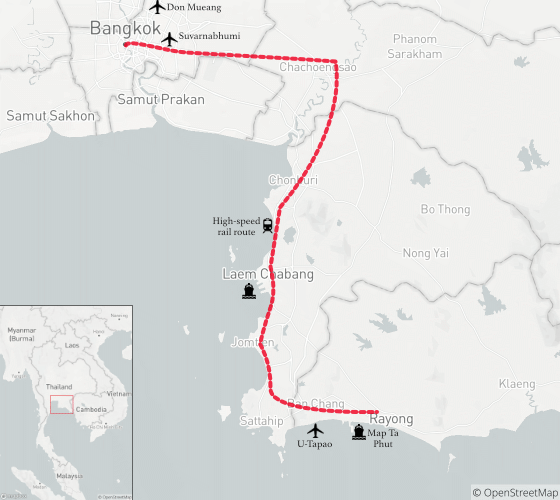

China is currently developing dual-railway tracks linking Bangkok to Nakhon Ratchasima, a major city in northeastern Thailand, which are likely to be extended to the Thai-Laos border town of Nong Khai in future. The rail route will connect to the EEC via another 225-billion-baht (US$7 billion) high-speed rail project linking Bangkok’s two international airports, Don Mueang and Suvarnabhumi with U-Tapao airport in eastern Rayong province.

On the maritime route, the Thai government plans to expand the capacity of two deep seaports in the eastern region that are also align with the BRI – Laem Chabang Port phase three in Chonburi, Map Ta Phut Industrial Port phase three in Rayong.

Both ports are listed in the four EEC infrastructure projects, along with high-speed rail and U-Tapao International Airport in Rayong, which the Thai government recently asked private firms to tender for.

The government expects EEC projects to generate total investment of 500 billion baht (US$1.5 billion), and be built by public-private partnerships, entities with durations of 30 to 50 years.

Thailand’s Eastern Economic Corridor

Winners and losers

On 12 November, the EEC Office revealed bidders for the high-speed rail project linking the three airports. The Thai conglomerate Charoen Pokphand Group has formed a consortium that includes China Railway Construction Corp Ltd, Italian-Thai Development PCL, and CH Karnchang PCL.

Another bidder is Thailand’s BRS Joint Venture, comprising of BTS Group Holdings, Sino-Thai Engineering and Construction and Ratchaburi Electricity Generating Holding.

“China is likely to get shares in most of the infrastructure projects,” says Somnuck Jongmeewasin, an independent community researcher based in eastern Thailand.

According to Somnuck, China’s rising influence in the EEC is partly because other foreign companies are reluctant to make new investments given the ongoing unrest in Thai politics under the military government and potential for local opposition

“China has no concern for Thai dictators, who can fast-track procedures and environment impact assessments and award privileges for investors without consulting local opinion,” says Somnuck.

Even though the EEC promises over 100-billion-baht annual investment in return, the big question is how it will distribute benefits to everyone from local to national level.

There is no clarity on EEC processes on the ground

Beyond Thailand’s major conglomerates, local businesses are as much in the dark as the farmers. They are short of information about the exact locations of industrial zones or railways, detailed project timeframes or when agriculture land-use zoning will be legally fixed to permit industrial development.

Overall, the EEC will boost the Thai economy says Meesak Chunharuckchote, chief executive of Chonburi Real Estate Association. “But the problem is, there is no clarity on EEC processes on the ground. There are some local investors who want to invest in the EEC but they don’t see how they can engage with it at the moment.”

After parliament passed the EEC legislation in mid-2018, the real estate industry was among the first to feel the impact with a wave of speculative land purchases. “Land prices are double,” says Meesak, who cautions new developments will take many years.

In rural Chachoengsao, home to rice farmer Prakob’s family, land prices have soared this year as buyers bet on the planned smart-city of two million people with new universities, a digital educational centre, and good transport links, confirms Jompong Chutabtim, secretary-general of Chachoengsao Chamber of Commerce.

He worries about whether there will be a well-balanced development that serves people’s needs, especially given the lack of consultation: “Through the EEC, the government is selling dreams to local people. We welcome the changes but they must be for the better, not for the worse,” says Jompong.

![Shahzad Qureshi standing inside his urban forest [image by: Zofeen T. Ebrahim]](https://dialogue.earth/content/uploads/2018/04/IMG_1295-300x225.jpg)

![Two fishermen on the Brahmaputra, a river that winds through four countries [image by: Sumit Vij]](https://dialogue.earth/content/uploads/2018/04/Brahmaputra-300x200.jpg)